Ameer Shahul

Israel started this war, not only by invading Palestinian land way back in 1948 but also with its recent actions.

Israel has been behind Iran for a while. Singularly and jointly with its partner in crime, the US. Israel played a key role in the assassination of Qassem Soleimani, the head of the IRGC’s Quds Force, responsible for Iran’s operations outside its borders five years ago. He was killed in a U.S. drone strike in Baghdad on January 3, 2020, with Israeli intelligence providing crucial information for the operation.

This was followed by the assassination of another key Iranian asset the same year. Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, Iran’s top nuclear scientist and a key figure in the country’s nuclear program, was killed by a covert operation on November 27, 2020, near Tehran, widely attributed to Israel’s Mossad.

After a pause during the peak of COVID, Israel resumed targeting Iranian assets whenever and wherever possible. Colonel Sayyad Khodaei, another senior officer in the IRGC, was killed outside his home in Tehran in May 2022. Shortly afterward, Hassan Sayyad Khodaei, another IRGC officer linked to the Quds Force, was killed in what was described as a ‘precision assassination,’ apparently for his involvement in planning attacks against Israeli targets abroad.

Iran did not openly retaliate against any of these actions. The reason: it was planning, or was assisting in planning, something ‘very, very big’ that Israel, despite its advanced human and digital surveillance network, could not pick up. This planning materialised on October 7, 2023, catching Israel off guard, despite being one of the most fortified and secure countries in the world.

In retaliation for the October 7 attack, Israel began a mass killing of Palestinian civilians. By October 7, 2024, at least 42,000 Palestinians had been killed, along with 2,000 in Lebanon. Over 100,000 people have been injured in what is widely considered one of the worst genocides unleashed in modern history.

Finding Iran’s open support to Hamas and Hezbollah behind the October 7 attack, Israel launched a major airstrike on the Iranian consulate annexe in Damascus, Syria killing senior IRGC commander Mohammad Reza Zahedi along with other Iranian and Hezbollah officials. Zahedi, a senior IRGC commander, was part of Israel’s broader effort to weaken Iran’s influence and military operations in Syria. This marked a direct escalation in the conflict between Israel and Iran, with Iran promising retaliation.

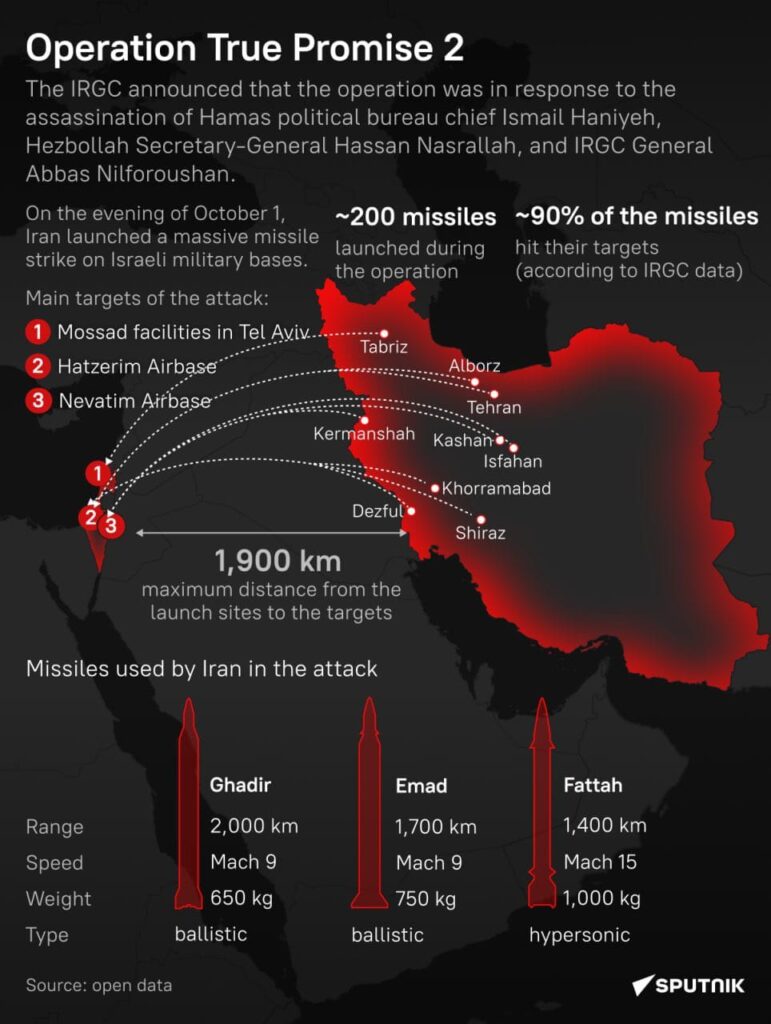

While the genocide in Gaza continued unabated, the prospect of a direct conflict between Israel and Iran became increasingly likely, creating a deeply troubling scenario in an already tense Middle East. With tensions increased after the killing of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah and further incursions in Lebanon, Iran had no option but to demonstrate its might. It did so by sending a barrage ballistic of missiles deep inside Israel and including a daring attack on the headquarters of Mossad.

It is now the turn of Israel. It has to respond one way or another. Israel has been talking about a pre-emptive strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities for a long to paralyse Iran’s atomic capabilities. The current situation is a precious opportunity for Israel which it doesn’t want to waste.

If Israel were to attack Iran with missiles and drones, the question arises: what are Iran’s options for a response? Would it go nuclear as the world fears? What challenges would it face in mounting such a response, and what are the wider strategic implications for the region?

Israel’s strategy has historically included pre-emptive strikes to neutralise existential threats, as evidenced by its attack on Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor in 1981 and Syria’s nuclear facility in 2007. The same doctrine applies to Iran, and Israel might use the opportunity to destroy Iran’s nuclear facilities and arsenal if it had already developed and stockpiled nuclear weapons.

An Israeli strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities would likely target key infrastructure such as the nuclear enrichment plants at Natanz and Fordow, along with other sites crucial to Iran’s nuclear program. Israel’s air force has conducted long-range training missions specifically for such scenarios, and it possesses advanced weapons, including the bunker-buster bombs required to penetrate Iran’s fortified underground facilities.

If Israel were to launch a strike without attacking its nuclear facilities, Iran’s options for retaliation could be a conventional military response. In such a scenario, Iran would rely on its conventional forces to retaliate. This could include launching missile strikes against Israeli cities, military bases, or critical infrastructure. However, Iran’s conventional military capabilities, while significant, would be unlikely to match Israel’s advanced technological superiority and air defence systems, including the Iron Dome and David’s Sling, which are designed to intercept incoming missiles.

However, if there is any attempt to take down its nuclear stockpile or destroy its nuclear capabilities, Iran would strike back with a nuclear arsenal. Let us analyse Iran’s current nuclear and military capabilities, its strategic options, and the significant obstacles that would impede any nuclear retaliation.

Iran’s nuclear program has long been a subject of international scrutiny and concern. Despite its claims that the program is for peaceful purposes, many intelligence agencies and governments, particularly in the West, believe that Iran has been inching closer to a weapons capability. Iran has developed significant uranium enrichment capabilities, especially after the 2018 U.S. withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), commonly known as the Iran nuclear deal.

Iran has enriched uranium well beyond the limits set by the JCPOA, at levels close to weapons-grade uranium, almost 90% pure. While it has not officially crossed this threshold, estimates have been suggesting for years that if Iran chose to “break out,” it could produce enough fissile material for a nuclear weapon within a few months. Producing weapons-grade material is only one aspect of developing a nuclear weapon. Constructing a functional nuclear warhead that can be mounted on a missile and reliably detonated involves additional technical challenges. There is no definitive public evidence that Iran has successfully developed or tested a fully detonatable nuclear warhead. Some earlier estimates had suggested that if Iran decided to build a nuclear weapon, it could develop a detonatable warhead in a matter of months.

There is no conclusive evidence that it has developed a fully operational nuclear warhead, but everyone from Biden to Netanyahu believes that Iran has nuclear warhead capability. The construction of a nuclear warhead requires a high level of technical expertise, and integrating that warhead into a missile is a further complex task. While intelligence agencies believe Iran has the knowledge and technology to achieve this, it is not proven or disclosed whether it has succeeded in doing so.

If it is considered that Iran possesses a nuclear warhead, the next question is how could it deliver it to Israel. It needs nuclear-capable long-range missiles.

Iran’s missile capabilities are formidable. Its missile arsenal includes both medium- and long-range ballistic missiles, such as the Shahab-3, which can reach Israel. Iran has invested heavily in its missile program over the years, with the aim of deterring Israel and other potential adversaries. However, in the absence of a fully developed nuclear warhead, these missiles were used only to carry conventional explosives.

To deliver a nuclear payload over Israel, Iran needs a near-perfect and non-detectable ballistic missile.

The challenge is that Israel’s missile defence systems, such as Iron Dome, David’s Sling, and the Arrow system, are designed to intercept incoming threats, including ballistic missiles. If a nuclear payload is intercepted in mid-air by an anti-missile missile, the outcome largely depends on the nature of the interception, the missile defence system in use, and the altitude at which the interception occurs.

Most importantly, a nuclear warhead will not detonate simply because it is hit by an anti-missile missile. Nuclear warheads require a precise series of events called fission chain reactions to detonate. These reactions are typically triggered by very specific conditions inside the warhead, such as the compression of fissile material using conventional explosives. A mid-air collision or explosion by a missile defence system would not cause these events to occur.

Therefore what can happen is a conventional explosion of warhead’s components. While the warhead itself would not trigger a nuclear explosion, the conventional explosives used to trigger the nuclear device might detonate due to the interception. This could result in a local explosion, but it would not be a nuclear explosion.

If a nuclear warhead is destroyed in mid-air, particularly if the interception occurs at a lower altitude, there could be dispersal of radioactive material such as plutonium or uranium from the warhead. This could create a so-called “dirty bomb” effect, spreading radioactive contamination over a local area, depending on factors such as altitude, wind, and interception location. If the interception occurs at a high altitude, the radioactive material might disperse into the atmosphere, with little immediate ground-level impact. If it happens closer to the ground, there could be localised contamination, posing health and environmental risks.

If the interception occurs in the upper atmosphere or at very high altitudes such as in the exe-atmosphere, there would likely be minimal radioactive fallout on the ground due to the thinning atmosphere. The debris could burn up upon re-entry, or it might slowly descend over a much larger area with limited impact. High-altitude explosions can have other consequences, such as creating electromagnetic pulses (EMPs), which could damage electronics and infrastructure over a wide area. However, for EMP effects to occur, the nuclear device itself would need to detonate, which is unlikely in an interception scenario.

If an interception happens at a lower altitude, closer to the ground, the radioactive material could fall to the Earth and contaminate a specific area. This could pose significant health risks, particularly if radioactive isotopes are inhaled or ingested by people or animals.

Therefore, intercepting a nuclear warhead in mid-air would not cause a nuclear explosion, but it might result in the dispersal of radioactive material, particularly at lower altitudes. The most sought-after situation would be a high-altitude interception, which would minimise the effects of any fallout. Advanced missile defence systems are designed to minimise these risks, but they cannot completely eliminate the dangers associated with the interception of a nuclear missile.

If Iran were to attempt delivering a nuclear payload to Israel, it has several potential options based on its current military capabilities. Iran’s ballistic missile arsenal would be the most likely delivery method due to its range, speed, and capability to carry a nuclear payload. The following missiles could potentially be used:

• Shahab-3: A medium-range ballistic missile with a range of approximately 1,300 kilometers (about 800 miles), capable of reaching Israel.

• Khorramshahr-4: An upgraded missile with a range of 2,000 kilometers (1,240 miles), more than enough to target Israel from Iran.

• Sejjil: A two-stage, solid-fuel missile with a range of around 2,000 kilometers, giving it the ability to reach Israel.

These missiles are highly mobile and difficult to intercept, making them a likely choice for long-range delivery.

Iran has also been developing cruise missiles, which are harder to detect and intercept due to their low-altitude flight. The Soumar cruise missile, with an estimated range of 2,000–2,500 kilometers, could potentially be adapted for nuclear delivery, though ballistic missiles remain more likely for such an operation.

Alternatively, Iran could potentially acquire a good delivery system from Russia, such as the RS-28 Sarmat (SS-X-30 Satan 2), which has a range of 18,000 km and is designed to evade missile defenses while carrying multiple nuclear warheads. Other options include the R-36M2 Voevoda (SS-18 Satan) with a 16,000 km range, and the Topol-M (SS-27 Sickle B) with an 11,000 km range, both capable of carrying nuclear payloads. Lastly, the Yars (RS-24), an improved version of the Topol-M, offers a 12,000 km range and can be deployed from silos or mobile launchers.

Iran also has the option to procure several advanced missile systems from Pakistan at short notice across its land border. The Shaheen-2 is a medium-range ballistic missile with a range of 1,500 to 2,000 km, capable of carrying multiple warheads; the Shaheen-3, currently under development, covers approximately 2,750 km. Additionally, the Hatf-5 (Ghauri) is an operational medium-range ballistic missile with a range of 1,250 to 1,500 km and the Ababeel missile with a range of 2,200 km designed to carry multiple independent reentry vehicles (to effectively evade missile defenses.

Bomber aircraft could theoretically be used to deliver a nuclear payload, but this would be a high-risk option for Iran. Israeli air defences, including advanced missile systems like the Iron Dome, David’s Sling, and Arrow systems, would make it challenging for an Iranian bomber to penetrate Israeli airspace. Naval vessels or submarines equipped with missile launchers could be used for a surprise attack, but Iran’s naval capabilities do not currently include submarines capable of launching nuclear-armed ballistic missiles over long distances.

In summary, ballistic missiles would be Iran’s most likely option for delivering a nuclear payload to Israel due to their range, speed, and proven capabilities.

(Ameer Shahul is an old-timer defence/technology correspondent with Press Trust of India, AFP and Reuters and is based in Bangalore, INDIA)